The Eurozone Crisis: Wrong diagnosis, harmful recipes

While the US recovery has been held back by inadequate policy measures, in the Eurozone (EZ) the policy response has been premised on a wrong diagnosis, thereby deepening the recession. The EZ periphery is, in effect, facing a balance-of-payments-cum-external-debt crisis resulting from excessive domestic spending and foreign borrowing of the kind experienced by several developing countries (DCs) in the past few decades. Contrary to the official diagnosis, the rapid increase in payments deficits and external debt that took place in the run-up to the crisis had little to do with fiscal profligacy (Lapavitsas et al., 2010; De Grauwe, 2010). With the exception of Greece, in all crisis-hit countries fiscal policy was tightened after 1999. During 2000-07 Spain and Ireland adhered to the Maastricht Treaty much better than Germany. Portugal had a relatively high deficit, but its debt ratio was not much higher than that of Germany (Table).

External debt is the key to the EZ crisis and the focus on total public debt is misleading (Gros, 2011). Belgium had a higher public debt ratio than Portugal, Spain and Ireland, but did not face any pressure and in fact enjoyed a low risk premium because it has had a sustained current account surplus and a positive net external asset position. Again, Italy is less affected than other periphery countries because it has had a much smaller current account deficit and a large proportion of its public debt is held domestically.

A common feature of the periphery countries in the Table is that they were all running larger current account deficits than all other EZ members in the run-up to the crisis. In Spain and Ireland, deficits were entirely due to a private savings gap. Even in Greece the current account deficit rose faster than the budget deficit because of a private spending boom.

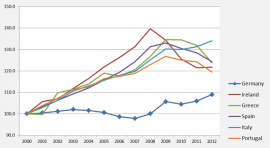

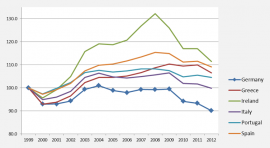

Two interrelated factors played an important role in rapid increases in current account deficits and external debt in the periphery. First, after the monetary union, wage and price movements diverged sharply between the periphery and the core (Chart 1). From early 2000 Germany was engaged in a process of “competitive disinflation”, keeping real wages virtually stagnant and reducing unit labour costs and relying on exports for growth (Akyüz, 2011; Palley, 2013). Improved German competitiveness was not always due to a superior productivity growth and wage suppression played a central role. By contrast, in the periphery wages went ahead of productivity, leading to an appreciation of the real effective exchange rate and loss of competitiveness (Chart 2). This created a surge in imports, mainly from other EU countries.

This process was greatly helped by a boom in capital flows from the core to the periphery, including loans from German banks, triggered by the common currency and abundant international liquidity (Sinn, 2011). They fuelled the boom in domestic demand, reduced private savings and widened the current account deficits in the periphery (Atoyan et al., 2013). They also helped Germany to increase exports and hence maintain a higher level of activity than was possible on the basis of domestic demand. As in Latin America in the early 1980s, this process also ended with an external shock from the US, this time the sub-prime crisis, which caused a panic turnaround in creditor sentiments and a sharp cutback in lending.

Monetary policy interventions in response to the EZ crisis have followed broadly the same course as in the US. Alongside the sharp cuts in policy rates, the European Central Bank (ECB) has undertaken several rounds of quantitative easing (QE), purchasing sovereign bonds in order to boost their prices and lower borrowing costs to troubled debtors. It also provided three-year loans to banks at low interest rates under the Long-Term Refinancing Operations (LTRO), enabling them to buy high-yield sovereign bonds and earn large spreads. In summer 2012, soon after its head reaffirmed the pledge to “do whatever it takes” to save the single currency, the ECB announced that it would undertake outright monetary transactions (OMT) in secondary sovereign bond markets subject to certain conditions, creating a wave of optimism in financial markets.

Several bailout facilities have also been introduced in response to the crisis including the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), European Financial Stabilization Mechanism (EFSM) and finally the European Stability Mechanism, a permanent bail-out fund to replace both the EFSF and EFSM. These facilities have been used, together with IMF lending, to keep debtors current on their payments to creditors and avoid default and to lower borrowing costs through bond purchases in secondary markets. The biggest rescue operation has so far been in Greece (some €170 billion), followed by Portugal (€78 billion), Ireland (€68 billion), Spain (€42 billion) and some €17 – €23 billion for Cyprus (Fidler, 2013). These operations incorporated severe retrenchment and austerity measures in recipient countries in the form of tax hikes, spending and wage cuts, leading to a deepening of contraction. In a subsequent evaluation of the 2010 Stand-By agreement for Greece, the IMF (2013c) has admitted that it had underestimated the damage done to the economy from spending cuts and tax hikes imposed in the bailout and that it deviated from its own debt-sustainability standards and should have pushed harder and sooner for lenders to take a haircut to reduce Greece’s debt burden.

Indeed, despite occasional references to the need to involve the creditors in the resolution of the crisis, the initiatives taken in this respect have brought limited relief to debtors. In early 2012 Greece was lent for debt buy-back to convert high-rate short-term bonds to low-rate long-term bonds and to reduce its stock of debt through a voluntary debt restructuring, as a one-off measure. However, it has not removed the Greek debt overhang. It is generally recognized that Greece needs a deeper write-off. However, around 70 per cent of its sovereign debt is now held by the official sector, including the EFSF, ECB, IMF, national central banks and other EZ governments, and the write-down of this debt is resisted by the ECB and Germany.

The EZ has not been able to follow a coherent approach in bailing in creditors and politics has often interfered with decisions in this regard. In Ireland and Spain where the crisis originated in the banking system, creditors and depositors of troubled banks have largely escaped without a haircut. Ireland gave a blanket guarantee to its bank depositors and Greek workouts also spared deposit holders both at home and abroad. In most of these cases rescue operations involved large amounts of money to prop up and recapitalize banks. By contrast, in Cyprus the bailout package inflicted large losses on deposit holders, notably Russians.

A key problem faced in the EZ is destabilizing interfaces between private and public debt. In Greece debt write-off caused difficulties in local banks as one-third of the discounted debt was held by them. Thus the operation necessitated recapitalization with new borrowing, thereby raising public debt. In Spain and Ireland governments have had to act to rescue heavily indebted banks and this has added significantly to public debt, increasing its financing needs. However, the very same banks are also expected to play an important role in financing heavily-indebted governments. Unable to print national currency, governments have limited capacity to bail out banks or monetize their own debt. A solution could have been to decouple public from private debt by stopping bank bailouts by national governments and introducing an EZ-wide bank resolution mechanism including bailing-in private creditors, recapitalization and liquidation (Burda et al., 2012).

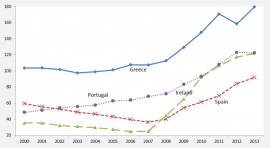

Public debt ratios have been rising in the periphery because of severe recession and relatively high interest rates (Chart 3). In Spain and Ireland the downward trend in debt ratios has been reversed whereas in Portugal the increase has accelerated after 2008. The Greek debt ratio has started to rise again after the decline brought about by the partial write-off. A fundamental dilemma is that when the ratio of debt to GDP is high and the real interest rate on debt exceeds the growth rate of GDP by a significant margin, the amount of primary surplus needed to stabilize the debt ratio would be quite high. Cuts made in the primary (non-interest) budget to achieve this would create a sizeable contraction in output because of relatively large fiscal multipliers noted above, making the task even more difficult. Thus, debt ratios of Spain and Ireland, which were both well below the 60 per cent threshold on the eve of the crisis, have reached 100 per cent and 120 per cent, respectively. For the same reason, the intensification of fiscal consolidation has not always resulted in lower deficits as a per cent of GDP. In Greece deficits rose from 9.5 per cent of GDP in 2011 to 10 per cent in 2012 and in Portugal from 4.4 to 6.4 per cent.

In view of the key role played by external debt and deficits in the EZ crisis, payments adjustment as well as debt restructuring is essential for the periphery to achieve a sustainable external position based on the expansion of exports. In this respect the periphery faces the additional problem of having been locked in a currency whose nominal exchange rate is beyond their control. Consequently, the only way to restore competitiveness is through cuts in wages. This problem was encountered by Argentina in the 1990s when it had fixed the peso against the dollar under the Convertibility Plan, which eventually culminated in default. So far the periphery countries with overvalued currencies have achieved a certain amount of internal devaluation and adjustment in their unit labour costs through wage suppression (Charts 1 and 2). They have also achieved significant improvements in their current accounts. However, much of these improvements have come from economic contraction, cuts in private investment and imports (Atoyan et al., 2013). Unemployment would need to remain high in order for wages to be kept under control and for unit labour costs and real exchange rates to continue declining. This may face serious social and political obstacles and could eventually lead to default and exit, as in Argentina.

Table: Pre-Crisis Debt and Deficits in the Eurozone (Per Cent of GDP)

| Fiscal Bal.(2000-07) | Public Debt( 2007 ) | Priv. Bal.(2000-07) | CA Balance(2000-07) | |

| Greece | –5.6 | 107.3 | –2.8 | –8.4 |

| Italy | –3.0 | 103.3 | +2.4 | –0.6 |

| Portugal | –4.1 | 68.3 | –5.2 | –9.3 |

| Spain | +0.4 | 36.3 | –6.2 | –5.8 |

| Ireland | +1.4 | 25.0 | –3.3 | –1.9 |

| Germany | –2.3 | 65.4 | +5.5 | +3.2 |